Me Chinese, Me Play Joke

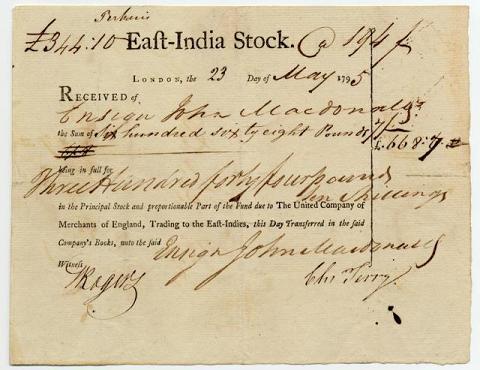

There is an extensive and complicated history of fascination with 'Eastern' artifacts and culture in the West. Invariably, the perfumed and exotic trappings of the 'Orient' captured the imaginations (and pocketbooks) of worldly aristocrat and street vendor alike. The East India Companies of prominent European merchant states led to the first big wave of Chinese themed decoration in the late 17th century and its culmination in the Rococo Chinoiserie of the 1700s.

This fascination continued unabated into the tile paneled Aranjuez of Spain, the late-Baroque palaces of Germany, and the parlors of Victorian England. It may come as no surprise that the flavor of the Orient also made its way into popular entertainment. But whereas the wide-eyed embrace of 'Orientalism' in its material form was pervasive, the Darwinian sociological fashion of the time assured that the "mysticism and primitivism" of the Orient was viewed through the prism of a highly xenophobic Europe.

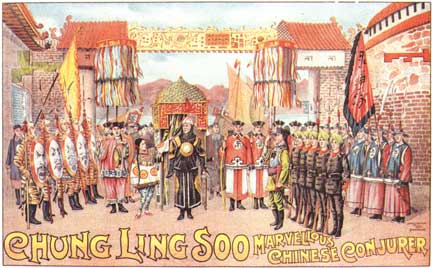

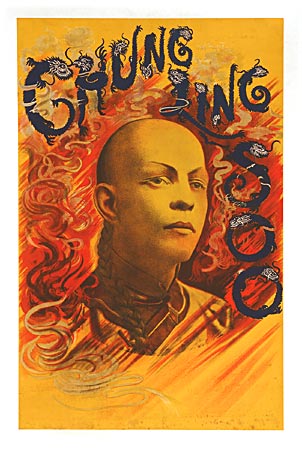

Performers who adorned themselves with the spoils of the Orient compelled and mesmerized audiences of all social classes. "Oriental" music and dances were performed with zeal (not to mention a conspicuous lack of authenticity) by spectacularly made-up individuals of definitively European descent. This approach preserved the necessary buffer zone for a kind of vicarious acculturation in an age where asians were generally feared and despised in equal measure by the populations at large - an age where even U.S. President Chester Arthur referred in official correspondence to the "hated Chinee." Performers who lifted that barrier and dared to BECOME oriental in the eyes of the crowds (or, god forbid, were ACTUALLY asian) walked a fine and dangerous line between terror and wonder: managing audience expectation.

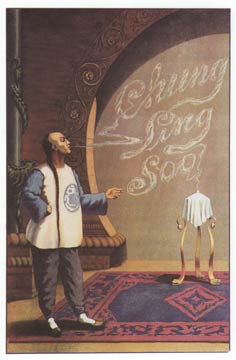

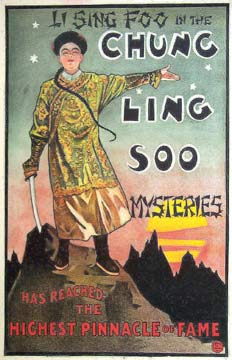

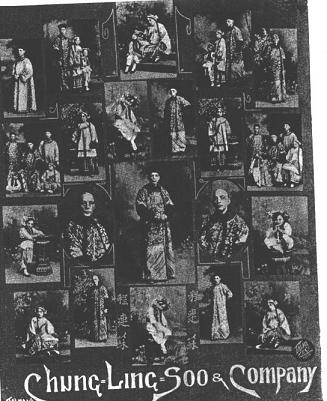

In the golden age of the vaudeville music hall, one performer in the "Oriental arts" gained notoriety above all others: the illusionist, Chung Ling Soo. Soo used the aura of a mysterious and unknowable 'East' to great effect in his act. On stage he projected an image of a humble, stoic Chinese man - one whose mastery of magic and illusion seemed to be thrust upon him - he often seemed to not even be completely self-aware of the implications of his incredible abilities. He would thank audiences in broken english, 'Much glad'. An observer of his turn of the 20th century career noted that this humility made his act palatable to many who might otherwise have felt threatened by such an individual (an effect it may also have had on legitimate Chinese magicians like the conjurer - and likely nominal inspiration - Ching Ling Foo).

One source described a typical act:

A large glass cage was suspended above the stage. It was transparent and it was made clear to the audience that there was nothing above or below it. The case was revolved above the spectators heads. The magician, clothed in long robes fired three shots into the air. Suddenly, a slight, small, Asian lady materialised in the cage. She jumped out nimbly and bowed and smiled at the awestruck crowd.

Chung Ling Soo took coffee beans, rice and sawdust, mixed them together and produced cups of coffee. They were served to audience members. Flowers were produced from pots of sawdust, and dolls, flowers and brightly coloured paper magically appeared from an empty cauldron.

The slight Asian lady from the cage, reappeared in other amazing feats. In one, the illusionist used a gigantic witch’s cauldron. Into it, he threw dead chickens, rabbits, geese and pigeons. Then a fire appeared burning under the pot. The cauldron steamed in the heat and it’s contents boiled. Suddenly from the midst of the inferno, in the heart of the steam, chickens, rabbits, geese and pigeons, leapt from the pot. In a final incredible moment, Chung Ling Soo brandished his wand, and behold the lady from the cage appeared in the middle of the blazing cauldron. She stepped out, alive and unscathed.

In another illusion, the same lady stood centre stage, with a target behind her. The magician fired an arrow tied by string, which appeared to pass right through her body. She emerged from the trial unhurt. Four large dice were placed atop each other and a cylinder placed over them. After mere seconds, the cylinder was lifted and the lady had replaced the dice. The audience was astounded.

Fire eating was also part of the act. Chung Ling Soo lit many pieces of paper and ate them as they burned. He then swallowed a lit candle whole. Finally he crammed down his throat a large wad of cotton wool. He used a chopstick to push it far into the reaches of his gullet. It caught fire, he stuck out his tongue and the audience could see the cotton burning in his mouth. Amidst the smoke and flames he breathed out coloured paper, silk handkerchiefs and other brightly coloured objects. By all accounts this was the part of the act that he least liked to perform.

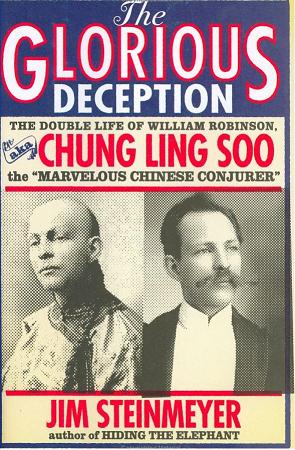

The accumulation of spectacular and seemingly impossible feats, when paired with the exotic presentation, terrified and delighted countless packed houses in the U.S. and abroad. Whether on stage or outside the hall, meeting with fans, telling tall tales of his homeland through an interpreter, or taking in local color, Soo cultivated a persona designed to inspire awe and encourage starstruck word-of-mouth gossip. Audiences believed, or wanted to believe, that Chung Ling Soo was completely genuine. But behind the carefully constructed artifice of a simple man from modest Cantonese beginnings, completely bewildered by the customs of the West, was a performer carrying out one of history's greatest cons: an American named William Ellsworth Robinson. Robinson would eventually bring this charade to its outrageous conclusion.

As Chung Ling Soo, Robinson worked for decades - he even entertained troops during World War I. But on March 23rd, 1918, while performing at the Wood Green Empire in London, the trick he was most known for - the Live Target Illusion - ended in tragedy. The illusion was significant and a source described it in detail: Two assistants, who would often dress like Boxers, would load marked bullets into a gun. They would fire the gun at the unprotected magician. He would then catch the bullets in his teeth and they would rattle into a plate that he held in his hands. When inspected, the bullets had marks identical to those that were placed in the muzzle of the revolver. Chung Ling Soo had performed this trick routinely for many years. That night something went wrong.

The muzzle-loaded guns were rigged such that the gunpowder charge fired in a chamber below the barrel so that the bullet never left the gun. This time, the trick gun was worn out and when the assistants fired as usual, some of the gunpowder exploded in the live chamber, setting off the loaded bullet which hit Soo in the chest. He fell to the ground. With a gasp he exclaimed, "My God, I’ve been shot, lower the curtain."

A bullet had pierced his right lung. William Ellsworth Robinson, now aged 58, had a wife - he also kept a secret mistress in London - but he had few friends. At this late stage, no one knew the real man, perhaps not even the man himself. He had disappeared into an enigma.

When Robinson died the following day, it marked the end of a chapter for a generation of men, women and children that had been rendered breathless by an impossibly exotic spectacle. They mourned, but they mourned Chung Ling Soo.

- Login to post comments