Vapour Portraits - Presidential Daguerreotypy

For years, I've wondered how far back the collection of past U.S. presidential photography must go.

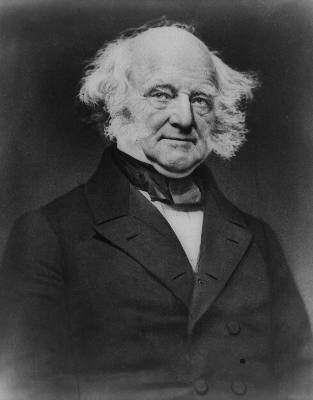

If you were to ask a random person on the street who the first president was to be photographed, off the top of their head some might say Abraham Lincoln. He is probably the earliest that most have seen, depending on the ghetto quotient of their high school history textbook. Some who blurt out a response before checking with their brain first might say George Washington, thinking of the spectacularly photograph-free $1 bill. The more historically-inclined moles among them may recall Martin Van Buren, he of the fish-gill-chops and our 8th president, who lived into the 1860s and was handsomely photographed late into his 79-year life.

None of the above are correct.

Presidential photography extends a generation back from the albumen prints of the civil war, to the early 1840s, before proper film negative photography, before the ferrotype or ambrotype. The daguerreotype was invented by French chemist Louis J.M. Daguerre, building on fellow frenchman Nicéphore Niépce's work with pewter and petroleum derivatives. Announced on January 9th, 1839, the process spread across the Atlantic to the U.S. in the years after.

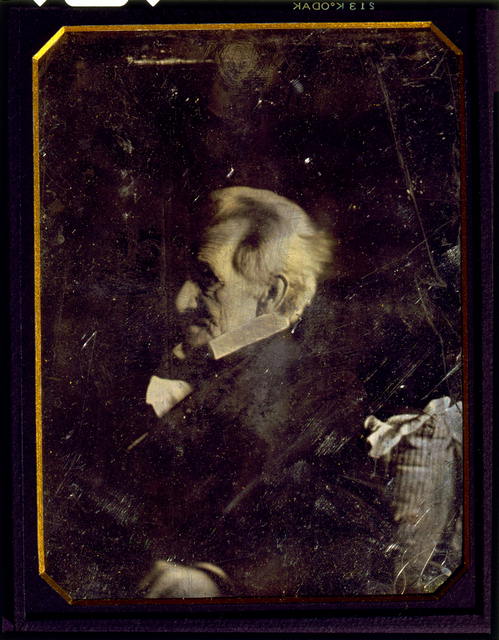

Daguerreotype photographs exist of presidents Zachary Taylor, James Buchanan, Franklin Pierce, James K. Polk, and Andrew Jackson, below:

The Library of Congress retains a stunning collection, viewable online.

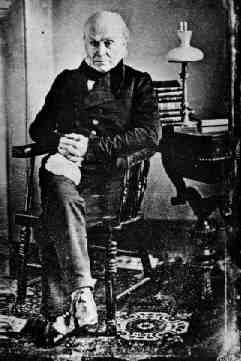

But what of the original question put forth? Who was the first? That honor goes to, amazingly, John Quincy Adams.

The 6th president of the United States, JQA lived long enough (died 1848) to be immortalized by this mercury vapor and silver iodide miracle. His predecessors James Madison (died 1836) and James Monroe (died 1831), numbers 4 and 5, met their end a hair too soon.

For many, presidential portrait photographs are the lasting (and sometimes only) memories of all pre-television-era presidents. Properly stored daguerrotypes can last forever as printed, and perhaps it's this fact that makes some of them so amazing. Surely these early photographers must have known they were in the process of nurturing the exposure of historic images that would be looked back upon centuries later as fruits of the birth of man's ability to capture a moment in time, forever.

Failing that realization, at least they could make wankable porn.

- Login to post comments

Comments

best pre-1850 look

My nominee for the most stylish pre-1850 public figure in the US was not a president, although he was just about everything else (congressman, senator, secretary of state, secretary of war, vice president): John C. Calhoun. Be thankful that daguerrotypy was invented in time to record his utterly awesome look:

While Google Image Searching

While Google Image Searching for more Calhounage, I found this awesome life mask of him. No hair, though.

What a shovel jaw!

He's like a blend of Christopher Walken and Willem Dafoe (I actually wrote "Willem Darfour" there at first, that's how scary he is!)

Colonial Technology

re: best pre-1850 look

Oh my god. If looks could kill, we'd all be all bubbly and molten right now. How the hell did he get so much volume in that hair? It's not a wig, is it?

simple..

vidal sassoon sr.

re: simple..

A-ha!

I guess I had him mixed up with Vidal Quincy Sassoon.

The Other Side of the Coin: Portraiture

John Quincy Adams

Doppelganger?

Imposter! (John Adams)

Gaze off-track (photo)

Gaze "fixed" by artist (Hale Woodruff)

Photos capture, for the most part, reality. One the one hand, we have these iconic images of perfectly coiffed men with perfectly proportioned facial features looking stolidly toward the future — and then we have the reality: men, growing older and weaker but perhaps wiser. The very moment that light hits that plate, the reality is revealed, and the flattering lie of the artist's conception is exposed. Perhaps the artist was hired specifically to catch the good side in the good light, or perhaps he simply thought it best, a healthy dose of subjective interpretation simply being a talent in itself.

I don't mind taking the god off the pedestal. It helps me to connect, to feel human somehow. You've already posted my favorite photo of John Quincy Adams. He's sitting in his chair with his legs crossed casually, and his gaze is still solid but no longer invincible — a man whose hand you could shake if you could reach back in time through that old plate. Artists had long captured his broad ponderous forehead, but sometimes changed his features utterly so that it seems like we're not even looking at the same man. [update: that's because it's a mis-labelled image of his father, John Adams]

My pondering is: How much have portrait artists had to change because they'd been caught out by the camera? And how much did they simply interpret (or lack portrayal talent) to begin with?

JQA, as you've said above, was the dividing line, so there's nothing from his youth to indicate whther his facial features changed so much. Modern portraiture still exists, though it's no longer a thriving enterprise. I see them from time to time, and I have to say, most of them are somewhere between egregious and god-awful. But, then again, if we wanted to savor the reality of every wrinkle and bump, we might simply turn away from the painter or charcoal artist and release the shutter of our cameras, and in an instant, capture the reality of our own image for all time.

And don't miss:

This one of Andrew Jackson.